How Antarctica’s history of isolation is ending—thanks to Starlink

Helpful hams and secret codes

By 1957,Admiral Byrd was recognized as the world’s foremost expert in Antarctic exploration and was leading America’s Operation Deep Freeze, a mission to build a permanent American presence on the continent. The US Naval Construction Battalions, known as the Seabees, were deployed to build McMurdo Station on the solid ground of Ross Island, close to the first hut built by Captain Robert Scott in 1901.

Deep Freeze brought a massive military presence to Antarctica, including the most complex and advanced communications array the Navy could muster. Still, men who wanted to speak to loved ones at home had limited options. Physical mail could come and go on ships a few times a year, or they could send expensive telegrams over wireless—limited to 100 or 200 words per month each way. At least these methods were private, unlike the personal communications over radio on Byrd’s expedition, which everyone else could listen in to by default.

In the face of these limitations, another option soon became popular among the Navy men. The licensed operators of McMurdo’s amateur (ham) station were assisted by hams back at home. Seabees would call from McMurdo to a ham in America, who would patch them straight through to their destination through the US phone system, free of charge.

Some of these helpful hams became legendary. Jules Madey and his brother John, two New Jersey teenagers with the call sign K2KGJ, had built a 110-foot-tall radio tower in their backyard, with a transmitter that was more than capable of communicating to and from McMurdo Sound.

To save money, a code known as “WYSSA” offered a broad variety of set phrases for common topics. WYSSA itself stood for “All my love, darling.”

From McMurdo, the South Pole, and the fifth Little America base on the Ross Ice Shelf, ham operators could ring Jules at nearly any time of day or night, and he’d connect them to home. Jules became an Antarctic celebrity and icon. A few of the engaged couples he helped to link up even invited him and his brother to their weddings, after the men returned from their tours of duty in Antarctica. Many Deep Freeze men still remembered the Madey brothers decades later.

In the early 1960s, continued Deep Freeze operations, including support ships, were improving communication across American outposts in Antarctica. Bigger antennas, more powerful receivers and transmitters, and improvements to ground-to-air communication systems were installed, shoring up the capacity for scientific activity, transport, and construction.

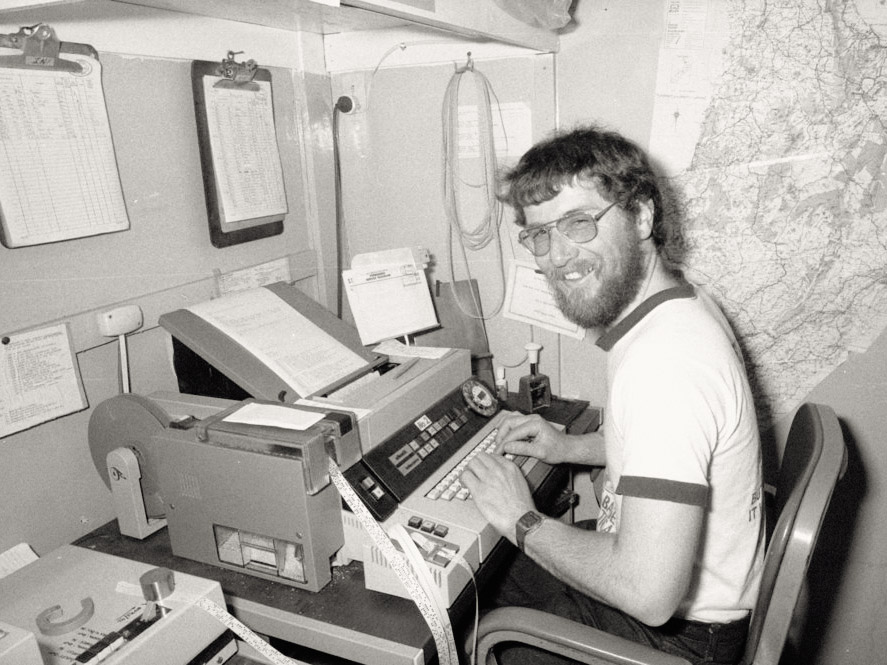

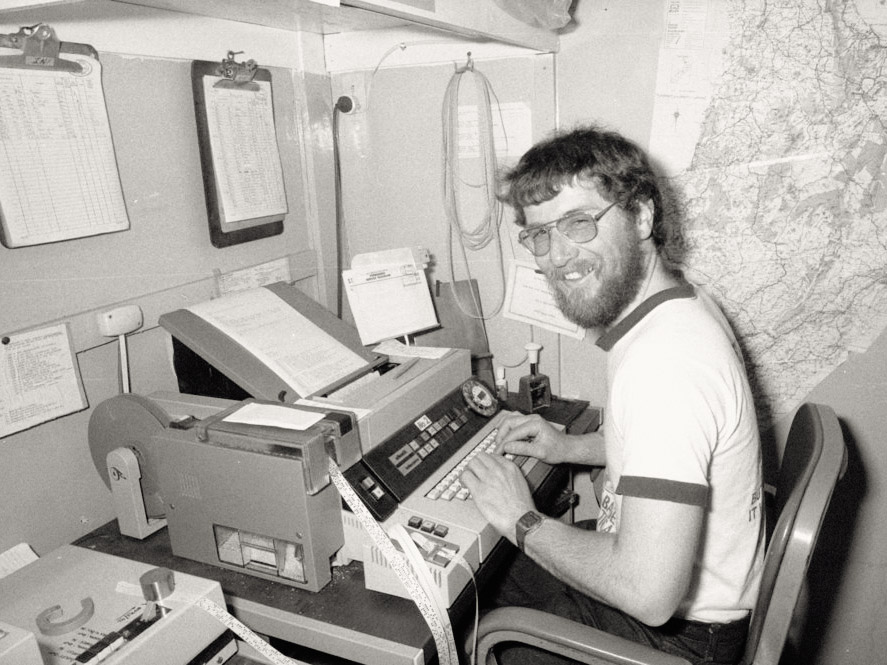

Around this time, the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions were improving their communications capacity as well. Like other Antarctic programs, they used telex machines, sending text out over radio waves to link up with a phone-line-based system on land. Telex, a predecessor to fax technology, text messaging, and email, was in use from the 1960s onwards as an alternative to Morse code and voice over HF and VHF radio. On the other side of the line, a terminal would receive the text and print it out.

MALCOLM MACFARLANE ©ANTARCTICA NEW ZEALAND PICTORIAL COLLECTION

In order to save money on the expensive per-word rates, a special code known as “WYSSA” (pronounced, in an Australian accent, “whizzer”) was constructed. This creative solution became legendary in Antarctic history. WYSSA itself stood for “All my love, darling,” and the code offered a broad variety of predetermined phrases for common topics, from the inconveniences of Antarctic life (YAYIR—“Fine snow has penetrated through small crevices in the huts”) to affectionate sentiments (YAAHY—“Longing to hear from you again, darling”) and personal updates (YIGUM—“I have grown a beard which is awful”).