Three people were gene-edited in an effort to cure their HIV. The result is unknown.

Vaccine makers have also struggled because HIV kills the very immune cells meant to stop infection. But a decade ago, Khalili says, he realized that CRISPR might offer a way to cure the infection without involving the immune system: by deleting the virus’s genes from their hiding places.

“If the viral gene is in your DNA, it becomes like a genetic disease,” he says. “And so you could use a genetic tool.”

Borrowed from nature

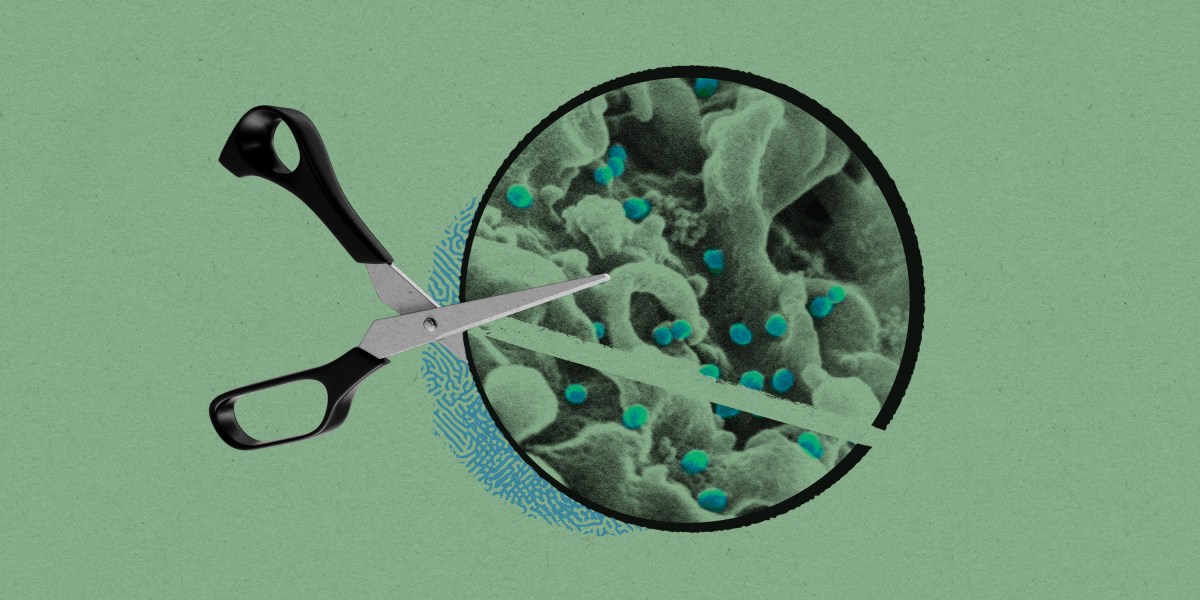

CRISPR technology was first developed in 2012 and was based on the discovery of molecules that bacteria use to spot and destroy incoming viruses, known as phages. It was quickly adapted to cut human DNA, launching the current era of human genome editing.

Most gene-editing studies getting attention today are those looking to treat inherited diseases, caused when people are born with faulty DNA. Exposing people to CRISPR can correct or remove those genes; one such treatment, for sickle-cell disease, is expected to win approval later this year.

Excision’s study is unusual in that it instead attempts to use gene editing to eliminate viruses. Among more than 50 gene-editing studies in human volunteers tallied by MIT Technology Review this year, only two involved infectious disease.

However, Khalili notes that zapping viruses was CRISPR’s original purpose in the wild. “Although the concept of using CRISPR against a virus looks novel, it stems from what was going on in nature already,” he says.

Initial lab tests showed that CRISPR could find and destroy the HIV genes in cells and, later, that it was able to functionally cure about 20% of HIV-infected mice treated with a gene-editing drug dripped into their veins, says Khalili.

The company won permission to begin human tests, and so far, three people have received the treatment. Each got an IV drip that released billions of harmless viruses carrying DNA instructions for making, and aiming, the CRISPR scissors.