China just fought back in the semiconductor exports war. Here’s what you need to know.

Mining companies in Congo and Russia have already said they intend to increase production of germanium to meet demand. Some Western countries, including the US, Canada, Germany, and Japan, also produce these materials, but ramping up production could be difficult. The mining process causes significant pollution, which was one of the reasons production was offshored to China in the beginning.

“The West will have to accelerate its innovation of new processes to separate and purify rare-earth metals. Otherwise, it may have to relax the environmental regulations that constrain traditional separation and purification techniques in the West,” says Chang.

Could China’s export controls be as successful as the American ones?

Probably not. Germanium and gallium can be mined elsewhere. But cutting-edge technologies are more restricted in their availability; the EUV lithography machines that the US wanted barred from export to China, for example, are made by a single company. “Export control is not as effective if the technologies are available in other markets,” says Sarah Bauerle Danzman, an associate professor of international studies at Indiana University Bloomington.

The US also has other advantages that make export control work more efficiently, she says, like the international importance of the dollar. The US chip curbs have an extraterritorial effect because companies fear being sanctioned if they don’t comply. They could be excluded from receiving payments in US dollars.

For China, the export controls could hurt its own economy, Bauerle Danzman adds, because it relies more on export trade than that of the US. Restricting Chinese companies from working with the rest of the world will undermine their business. “Unless [China] is going to get Japan and South Korea and the EU to agree to not trade with the US, in order for it to really execute on a strategy like this, it not only has to stop exports to the US—it has to stop exports to basically everywhere,” she says.

Has China restricted the export of critical raw materials before?

This is not the first time China has tried to restrict the export of raw materials. In 2010, it reduced the allotment of rare-earth elements available for export by 40%, citing an interest in environmental conservation. The same year, the country was accused of unofficially banning rare-earth exports to Japan over a territorial dispute.

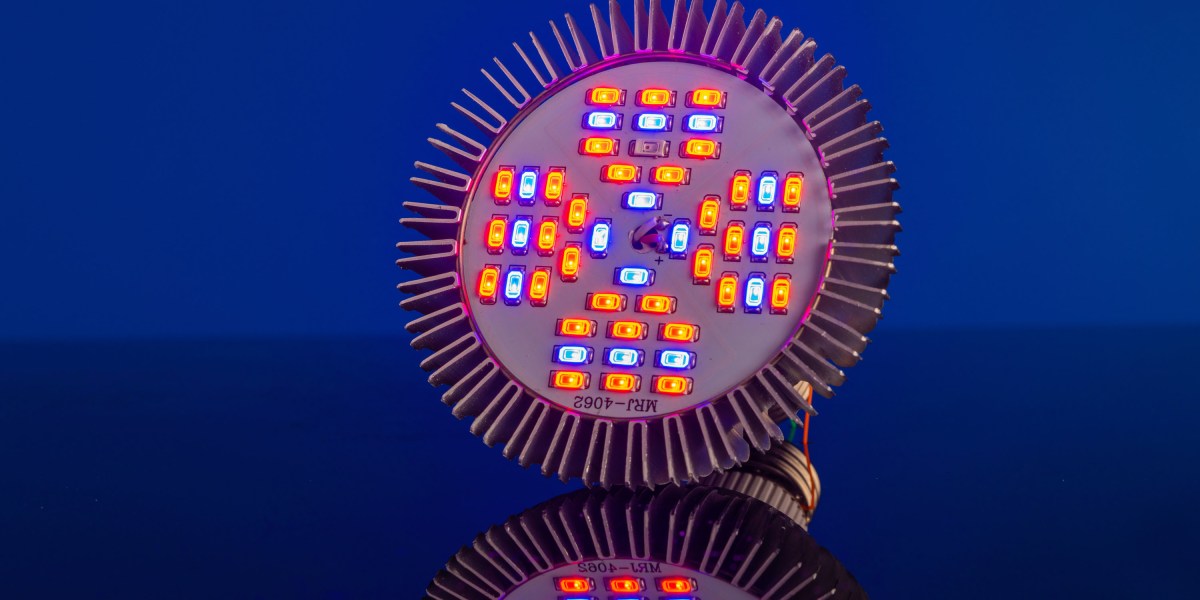

Rare-earth elements are used in manufacturing a variety of products, including magnets, motors, batteries, and LED lights. The quota was later challenged by the US, EU, and Japan in a World Trade Organization dispute. China’s environmental protection justifications didn’t convince the settlement panel. It ruled against China and asked it to roll back the restrictions, which happened in 2015.

This time, the Japanese government has again said it could raise the issue with WTO, but China likely won’t need to worry about it as much as the last time. With the rise in trade protectionism and self-preserving supply-chain policies during the pandemic era, the organization has increasingly lost its authority among member countries. “Today, WTO is less relevant, and China is trying to find a more nuanced policy argument to back up their actions.” says Lu.