New Method to Create 3D Printed Sensors Could Help Scientists Predict Weather, Study Climate Change

Researchers at the MIT have developed the ability to create low-cost plasma sensors for orbiting spacecraft. These 3D-printed sensors can be produced for tens of dollars in a matter of days. The 3D-printed plasma sensorsare ideal for CubeSats, which are used for environmental monitoring or and could help scientists weather prediction.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers have developed a way to create low-cost plasma sensors, which are the first to get completely manufactured digitally, for orbiting spacecraft. In contrast to the plasma sensors that get manufactured in a cleanroom, the 3D-printed sensors can be produced for tens of dollars in a matter of days. Due to the low cost and speedy production, the 3D-printed plasma sensors, also known as retarding potential analyzers (RPAs), are ideal for CubeSats, which are used for monitoring the environemnt or predict the weather.

In satellites, these plasma sensors are used to determine the chemical composition and ion energy distribution of the atmosphere. The inexpensive, low-power and lightweight satellites are often used for communication and environmental monitoring in Earth’s upper atmosphere.

As a reult, the sensors were created with complex shapes, using a glass-ceramic material, which can withstand the wide temperature swings a spacecraft would encounter in lower Earth orbit. The plasma sensors can help scientists predict the weather or study climate change.

Luis Fernando Velasquez-Garcia, a principal scientist in MIT’s Microsystems Technology Laboratories (MTL) and senior author of a paper presenting the plasma sensors, said, “Additive manufacturing can make a big difference in the future of space hardware. Some people think that when you 3D-print something, you have to concede less performance. But we’ve shown that is not always the case. Sometimes there is nothing to trade-off.”

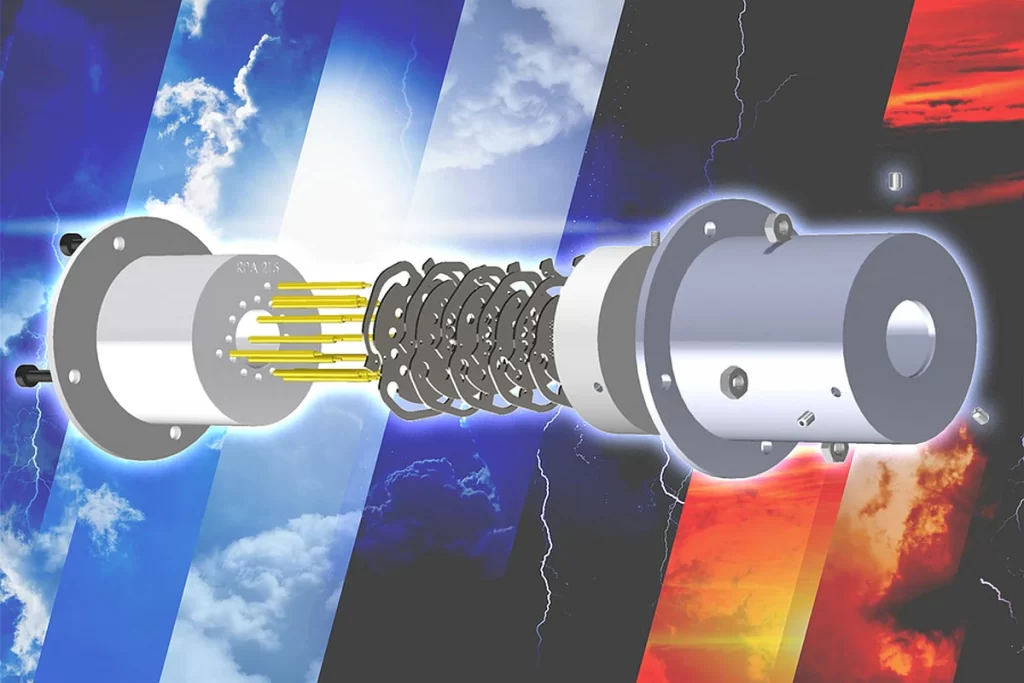

These plasma sensors have a series of electrically charged meshes, dotted with tiny holes. When plasma passes through the holes, electrons and other particles are stripped away and only ions remain. These ions create an electric current which the sensor measures and analyzes.

Velasquez-Garcia added, “When you make this sensor in the cleanroom, you don’t have the same degree of freedom to define materials and structures and how they interact together. What made this possible is the latest developments in additive manufacturing.”

The study has been published in Additive Manufacturing.