New fossils suggest land life bounced back faster than expected After End-Permian Mass Extinction

Fossil evidence has indicated that land ecosystems rebounded more quickly than previously thought after the end-Permian mass extinction, which occurred approximately 252 million years ago. The extinction event, known as the most severe in Earth’s history, led to the loss of over 80% of marine species and 70 percent of terrestrial species. Reports suggest that tropical riparian ecosystems, found along rivers and wetlands, demonstrated resilience by recovering within a shorter timeframe than earlier estimates, which ranged from seven to ten million years.

Sediment and Fossil Analysis Supports Findings

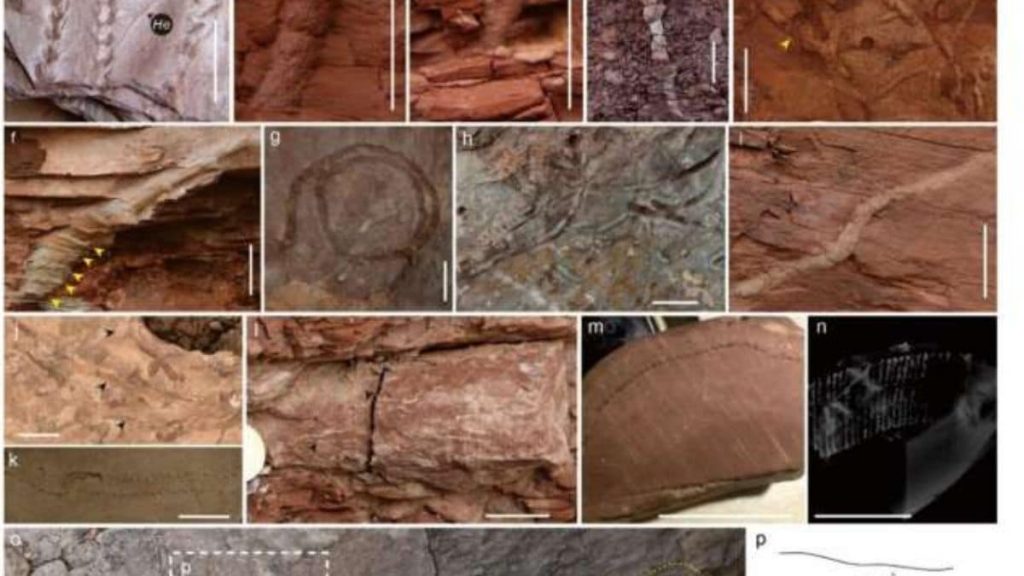

According to a study published in eLife, sediment and fossil records from the Heshanggou Formation in North China have provided evidence of a faster-than-expected recovery. Researchers examined sedimentary deposits from lakes and rivers, focusing on plant remains, vertebrate fossils, and trace fossils such as burrows and footprints. The research team, led by Dr. Li Tian, Associate Researcher at the State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology at China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, analysed fossil samples spanning the Early Triassic period, approximately 252 to 247 million years ago.

Findings indicated that at the onset of the Early Triassic, only a few species dominated the landscape, with significantly smaller organisms compared to pre-extinction life. The data pointed to a harsh environment with limited biodiversity. Fossils from the Spathian stage, around 249 million years ago, showed an increase in plant stems, root traces, and burrowing activity, suggesting the reestablishment of stable ecosystems. The presence of medium-sized carnivorous vertebrates was also recorded, indicating the formation of multi-level food webs.

Burrowing Behaviour Signals Ecosystem Stability

Burrowing activity, which had largely disappeared following the extinction event, was noted as a key indicator of recovery. Reports state that burrowing plays a critical role in soil aeration and nutrient cycling, facilitating ecosystem stability. The resurgence of this behaviour suggests that certain species adapted to environmental stresses by seeking refuge underground.

Senior author Jinnan Tong, Principal Investigator at the State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology, stated to phys.org that tropical riparian zones may have functioned as ecological refuges, providing stable conditions that allowed life to rebound faster than in drier inland areas. Further research is expected to determine whether similar patterns of recovery occurred in other regions during the Early Triassic.