Dismissal of Trump Classified Documents Case Checks the Power of Special Counsels

Less than 48 hours after surviving an assassination attempt, former President Donald Trump received a bit of good newswhich could have positive downstream effects for the rest of us, as well.

In 2023, Special Counsel Jack Smith brought a 42-count indictment over Trump’s “willful retention” of classified documents he was no longer allowed to possess after leaving office. Trump’s attorneys have argued, among other things, that Smith was improperly appointed to his position.

On Monday, Judge Aileen Cannon of the U.S. District Court for Southern Florida agreed and dismissed the case.

U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland originally appointed Smith in November 2022 to oversee two separate investigations of Trump, one pertaining to “efforts to interfere with the lawful transfer of power following the 2020 presidential election” and the other relating to classified documents.

“The Appointments Clause [of the U.S. Constitution] does not permit the Attorney General to appoint, without Senate confirmation, a private citizen and like-minded political ally to wield the prosecutorial power of the United States,” Trump alleged in a February filing. “As such, Jack Smith lacks the authority to prosecute this action.”

“The Appointments Clause requires that any appointment be with the ‘Advice and Consent of the Senate.’ It follows, then, that to properly establish a federal office, Congress must enact it,” the filing continued. “There is, however, no statute establishing the Office of Special Counsel. As a result, because neither the Constitution nor Congress have created the office of the ‘Special Counsel,’ Smith’s appointment is invalid and any prosecutorial power he seeks to wield is ultra vires”meaning, beyond his legal authority.

Cannon, whom Trump originally appointed to the bench, agreed: “The Appointments Clause is a critical constitutional restriction stemming from the separation of powers, and it gives to Congress a considered role in determining the propriety of vesting appointment power for inferior officers,” she wrote on Monday. “The Special Counsel’s position effectively usurps that important legislative authority, transferring it to a Head of Department, and in the process threatening the structural liberty inherent in the separation of powers.”

Cannon did not completely foreclose the possibility of prosecuting Trump in the documents case, but she held that the use of a special counsel “to investigate and prosecute this action with the full powers of a United States Attorney” would need to go through the proper channels, either by Senate confirmation or passing a law.

Federal agents first raided Trump’s Florida resort home in August 2022, turning up over 300 records marked as classified. The raid came after more than a year of discussions in which Trump brushed off requests from the National Archives and Records Administration to return missing documents.

Cannon became involved in the case soon after, when she granted Trump’s request that a “special master” review the documents and verify if they were actually classified. Trump based his request on the premise that in fact he had secretly declassified all of the documents while leaving office, a theory Reason’s Jacob Sullum called “implausible” and “legally irrelevant.” The appointed special master disagreed with Trump, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit later reversed Cannon’s order, claiming that she had acted outside the scope of her authority.

Ever since, commentators have accused Cannon of being in the tank for Trump, or perhaps just in over her head. “It is wholly inappropriate to have somebody with that combination of bias and inexperience handling a case like this,” wrote MSNBC legal analyst Andrew Weissmann.

“Over and over,” Cannon “has treated seriously arguments that many, if not most, federal judges would have rejected out of hand,” wrote The New York Times’ Alan Feuer in May.

This week’s order will likely just pour gasoline on that fire. But taken as a whole, it could have positive downstream effects on the legal system.

Granted, the order as written would allow Trump to avoid consequences for his actionsretaining classified documents for no apparent reason other than a sense of entitlement, and obstructing the investigation, after making such political hay of his 2016 opponent’s alleged mishandling of classified emails.

But as it pertains to the appointment of special counsels, there are silver linings.

“A special counsel is supposed to ensure that the Justice Department can credibly conduct sensitive investigations that are and that appear to be fair and apolitical. Yet special counsels (and their precursors) have for decades failed to achieve this goal,” wrote Jack Goldsmith, a former assistant attorney general under President George W. Bush, in March. “It is time to kill the special counsel institution.”

“Good riddance,” agrees Josh Blackman, a constitutional law professor at South Texas College of Law Houston. “The concept that prosecution can be divorced from politics was always a fantasy.”

Indeed, the regulations governing special counsels afford enormous power. “They deny the attorney general ‘day-to-day supervision’ of a special counsel,” Goldsmith wrote. “And attorneys general tend not to want the ultimate responsibility…because it puts them more centrally in political cross hairs, which is contrary to the department’s ethos to appear apolitical. Checking special counsels’ excesses or failing to publish their reports invariably seems like political meddling or cover-up.”

Indeed, special counsels (and their predecessors, independent counsels) are routinely criticized for overstepping their authority in one direction or the other. As Goldsmith wrote, many criticized Whitewater Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr for “including salacious and politically damaging but legally irrelevant details in a referral to Congress that laid out grounds for [President Bill] Clinton’s possible impeachment.” And after a yearslong investigation into Trump’s potential ties to Russian interference in the 2016 election, Special Counsel Robert Mueller “drew justified criticism when he departed from the special counsel regulations by refusing to decide whether Mr. Trump had committed prosecutable crimes while commenting that his report did not ‘exonerate’ him.”

After all, special counsels are just prosecutors with different titles, and prosecutorseven when not exceeding their authorityare the single most powerful entities in the criminal justice system.

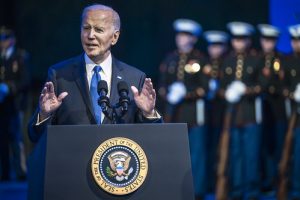

While the government is almost certain to appeal Cannon’s ruling, as written, it would have repercussions in other cases: Garland appointed U.S. Attorney David Weiss as special counsel in the ongoing investigations of Hunter Biden, the beleaguered son of President Joe Biden, using the exact same authorities as when he appointed Smith.