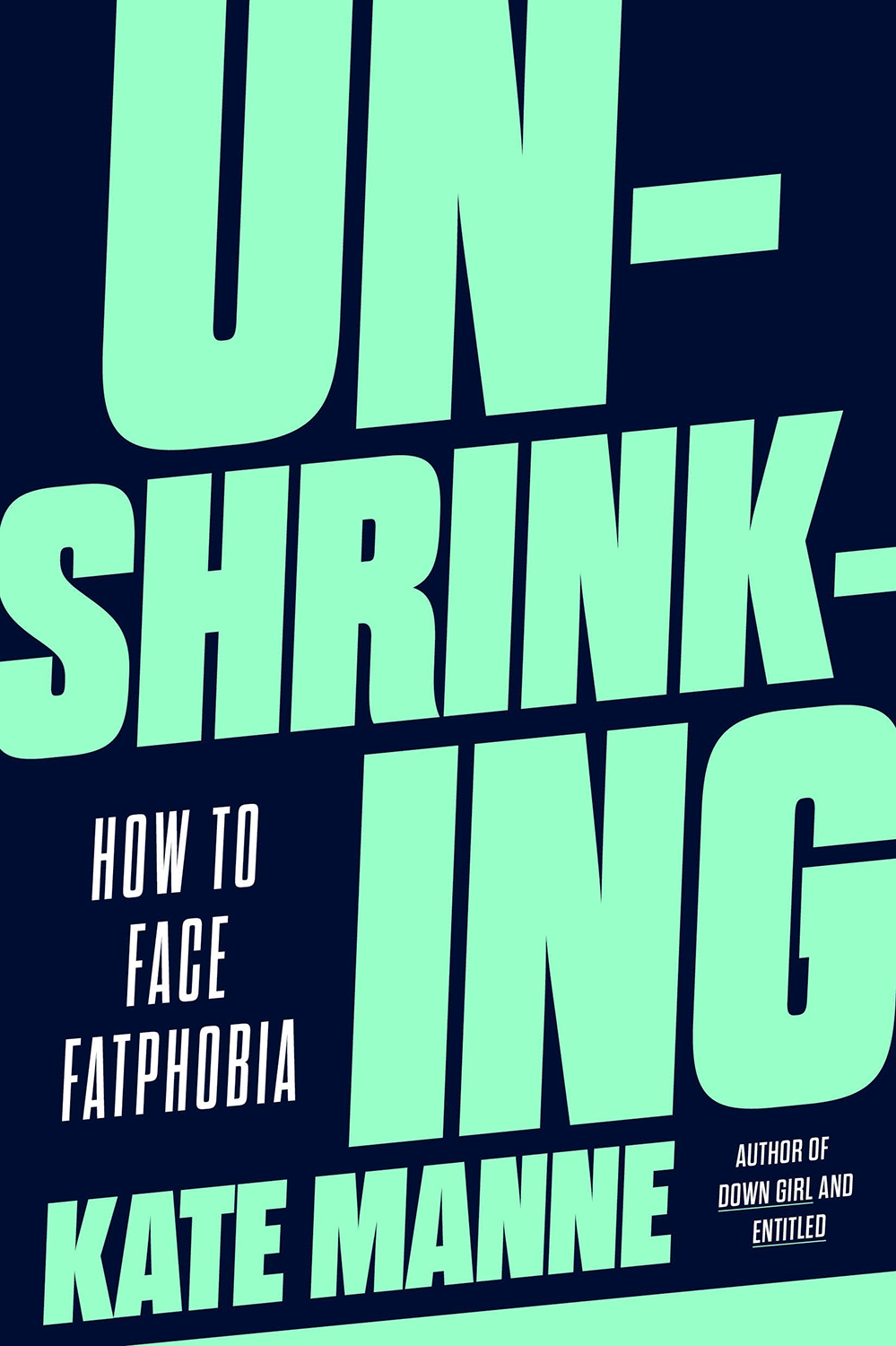

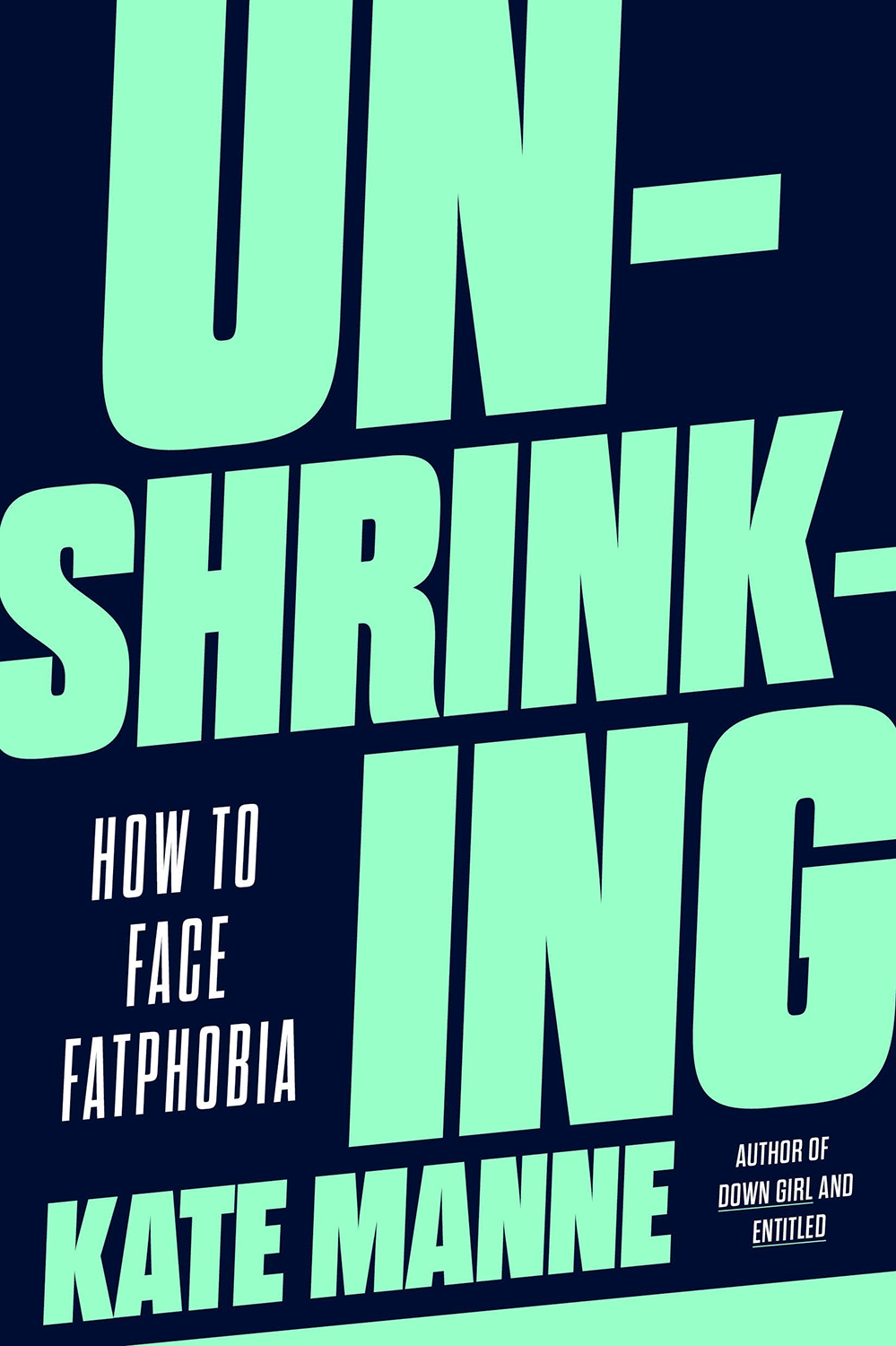

Fighting fatphobia

Unshrinking joins the growing literature on anti-fat bias, including the work of sociologist Sabrina Strings, whose book Fearing the Black Body details its racist origins, tracing the shift from the admiration of plumpness as a sign of wealth to the vilification of fat that she argues developed alongside the transatlantic slave trade. Like recent books by Aubrey Gordon and journalist Virginia Sole-Smith, Manne’s uses scientific research to debunk pervasive misconceptions—for example, about the extent to which people can control the size of their bodies—and even to counter the idea that obesity is a disease that requires a cure or large-scale policy response.

Research from as early as 1959 has shown that most people cannot sustain long-term weight loss. A recent piece in the journal Obesity finds that weight regain “occurs in the face of the most rigorous weight-loss interventions” and that “approximately half of the lost weight is gained back within 2 years and up to 70% by 5 years.” Not even those who undergo bariatric surgery, the researchers add, are immune to weight regain. Two physician researchers from Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania recently reported in Nature Metabolism, “Overall, only about 15% of individuals can sustain a 10% or greater non-surgical, non-pharmacological weight loss.”

Likewise, while exercise is beneficial for our bodies, a research review published in Diabetes Spectrum concludes it’s not firmly established that it plays a big role in helping people lose weight.

“I can tell you precisely what I weighed on my wedding day, the day I defended my PhD dissertation, the day I became a professor, and the day I gave birth to my daughter.”

And although the medical establishment has been saying for decades that obesity leads to diseases like diabetes and hypertension, Manne points out that the dynamics are complex and there is much that is still unknown. While being very heavy is correlated with increased mortality, she maintains that we cannot assume it is a direct cause. For example, researchers have found that diabetes is associated not only with obesity but with poverty, food insecurity, and even past trauma as well.

Manne’s argument is not that being fat is unassociated with health risks, but rather that the connection is oversimplified. Given that there’s no proven route to long-term weight loss for most people, she says, we should focus on treating people’s diagnosable problems (such as diabetes and heart disease) rather than stigmatizing them because of their size. But anti-fat bias is all too common among medical professionals, who often misdiagnose fat people’s actual health problems because they ignore their reported symptoms. The prospect of dealing with this prejudice can also discourage fat people from going to the doctor at all. In 2020, a review of scientific publications led an international multidisciplinary expert panel to conclude that weight bias can lead to discrimination, undermining people’s human and social rights as well as their health. The 36 experts pledged in Nature Medicine to work to end the stigma attached to obesity in their fields.

What is needed, Manne argues, is to dismantle diet culture, which not only does not make people thinner in the long term but appears to make them fatter: “The studies that I draw on in the book make a very clear empirical case that a really excellent way to gain weight is to diet.” For example, a 2020 review in the International Journal of Obesity suggests that dieting can lead to eventually regaining more weight than was lost, given how one’s metabolism reacts to food restriction. A better way to improve public health, Manne argues, is to reduce the bias against larger bodies and make public spaces more accessible for people of all sizes. While data on the potential effects is limited, one 2018 study suggests that a weight-neutral approach known as Health at Every Size (HAES) is beneficial for body image and quality of life.

As a philosopher, Manne offers novel insights by looking at the way fatness is framed as a moral issue. Western societies see fat people as moral failures because, it is assumed, they lack the willpower to eat healthy foods and exercise. Manne argues that we have been conditioned to feel disgust toward fat people, and that this disgust is both “socially contagious” and deeply ingrained. Furthermore, we don’t trust feelings of pleasure derived by eating, or we don’t believe we inherently deserve food that tastes good; instead, we think we have to “earn” it, usually by depriving ourselves. Indeed, most of us are subject to frequent moralizing about “good” and “bad” food—whether from friends, family members, or our own internal voices.

All of this is part of what Manne calls the “fallacy of the moral obligation to be thin.” Secular moral philosophy is “clear that happiness and pleasure are good things, which we should be increasing in the world and promoting,” she says. “There’s nothing shameful about something that feels good, that some people want intensely, as long as it doesn’t hurt others or deprive others.”

So if diet culture causes pain, deprivation, and eating disorders, Manne maintains, we have a moral obligation to avoid it and instead to derive pleasure from eating. She reasons, “If you do think of there being a kind of moral value in self-care, then we really ought to be satisfying our appetites by eating satisfying food, as well as nourishing our bodies for instrumental reasons.” In her book, she calls diet culture a “morally bankrupt practice.”

But Manne’s experience as a fat academic has shown that most highly educated people still cling tightly to the “pseudo-obligation to try to shrink ourselves,” she says. Stereotypes of fat people as lazy and dumb are particularly harmful in spaces where intellect is highly prized. Anti-fat bias is pronounced in her field, Manne believes, “because as much as we pretend in philosophy not to all be dualists, we value the mind much more than the body, and we’re deeply suspicious of the body.” Tracing this “philosophical disapproval of indulgence” back to Plato and Aristotle, she says: “We think of the body as something feminine, wild, out of control, irrational—not a source of wisdom, but a source of really antiphilosophical distraction that will prevent us from … using our minds to think deep thoughts.”