The return of pneumatic tubes

By the 1960s, pneumatic tubes were becoming standard in health care. As a hospital administrator explained in the January 1960 issue of Modern Hospital, “We are now getting eight hours’ worth of service per day from each nurse, where previously we had been getting about six hours of nursing plus two hours of errand running.”

As computers and credit cards started to become more prevalent in the 1980s, reducing paperwork significantly, the systems shifted to mostly carrying lab specimens, pharmaceuticals, and blood products. Today, lab specimens are roughly 60% of what hospital tube systems carry; pharmaceuticals account for 30%, and blood products for phlebotomy make up 5%.

The carriers or capsules, which can hold up to five pounds, move through piping six inches in diameter—just big enough to hold a 2,000-milliliter IV bag—at speeds of 18 to 24 feet per second, or roughly 12 to 16 miles per hour. The carriers are limited to those speeds to maintain specimen integrity. If blood samples move faster, for example, blood cells can be destroyed.

The pneumatic systems have also gone through major changes in structure in recent years, evolving from fixed routes to networked systems. “It’s like a train system, and you’re on one track and now you have to go to another track,” says Steve Dahl, an executive vice president at Pevco, a manufacturer of these systems.

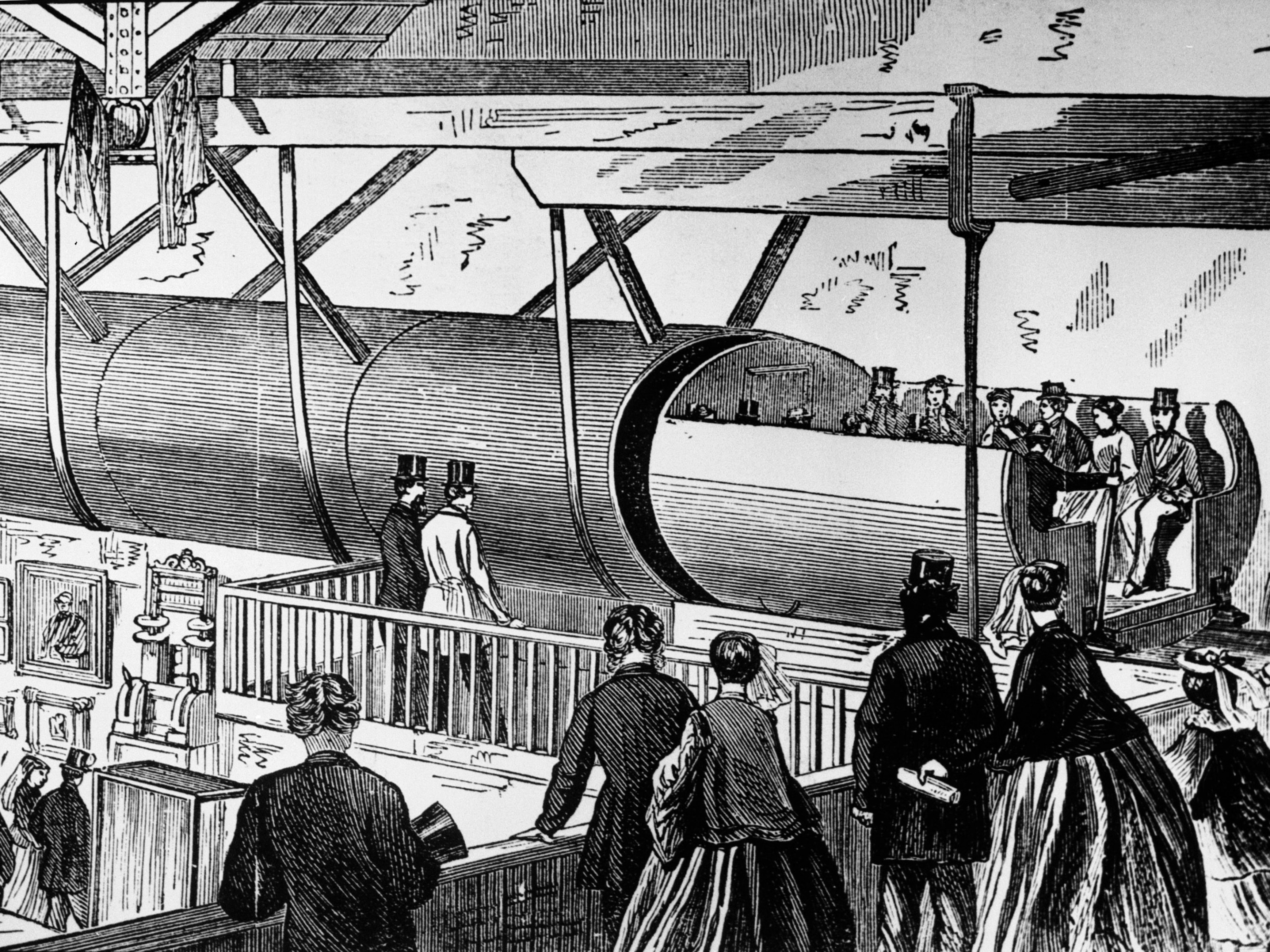

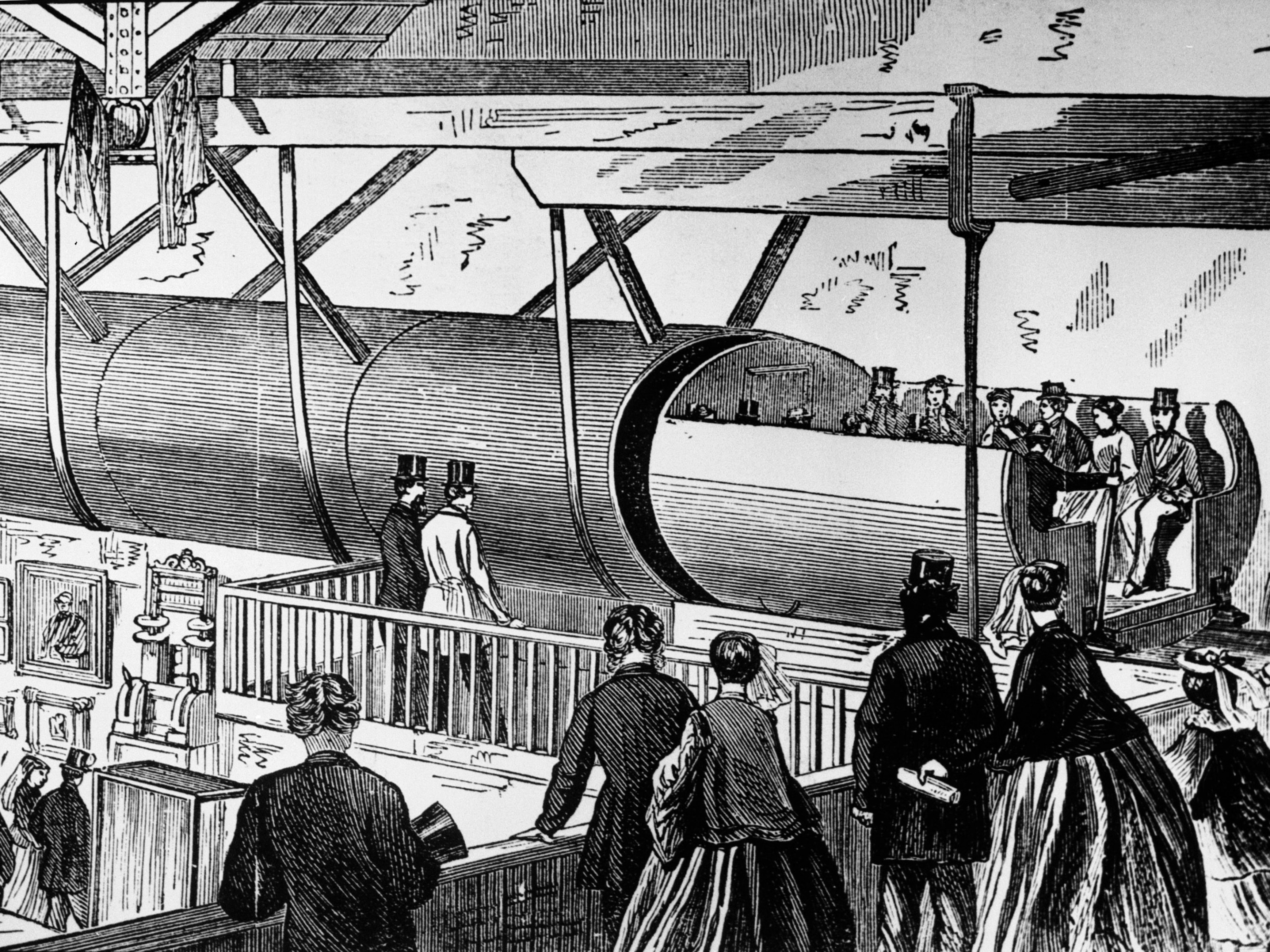

GETTY IMAGES

Manufacturers try to get involved early in the hospital design process, says Swisslog’s Kwarta, so “we can talk to the clinical users and say, ‘Hey, what kind of contents do you anticipate sending through this pneumatic tube system, based on your bed count, based on your patient census, and from where and to where do these specimens or materials need to go?’”

Penn Medicine’s University City Medical District in Philadelphia opened up the state-of-the-art Pavilion in 2021. It has three pneumatic systems: the main one is for items directly related to health care, like specimens, and two separate ones handle linen and trash. The main system runs over 12 miles of pipe and completes more than 6,000 transactions on an average day. Sending a capsule between the two farthest points of the system—a distance of multiple city blocks—takes just under five minutes. Walking that distance would take around 20 minutes, not including getting to the floor where the item needs to go.