The cost of building the perfect wave

Surf pools’ proponents frequently point to the far larger amount of water golf courses consume to argue that opposing the pools on grounds of their water use is misguided.

PSSC, the first of the area’s three planned surf clubs to open, requires an estimated 3 million gallons per year to fill its pool; the proposed DSRT Surf holds 7 million gallons and estimates that it will use 24 million gallons per year, which includes maintenance and filtration, and accounts for evaporation. TBC’s planned 20-acre recreational lake, 3.8 acres of which will contain the surf pool, will use 51 million gallons per year, according to Riverside County documents. Unlike standard swimming pools, none of these pools need to be drained and refilled annually for maintenance, saving on potential water use. DSRT Surf also boasts about plans to offset its water use by replacing 1 million square feet of grass from an adjacent golf course with drought-tolerant plants.

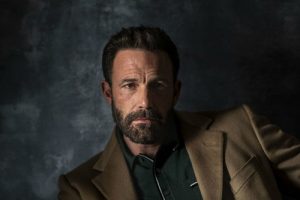

SPENCER LOWELL

With surf parks, “you can see the water,” says Jess Ponting, a cofounder of Surf Park Central, the main industry association, and Stoke, a nonprofit that aims to certify surf and ski resorts—and, now, surf pools—for sustainability. “Even though it’s a fraction of what a golf course is using, it’s right there in your face, so it looks bad.”

But even if it were just an issue of appearance, public perception is important when residents are being urged to reduce their water use, says Mehdi Nemati, an associate professor of environmental economics and policy at the University of California, Riverside. It’s hard to demand such efforts from people who see these pools and luxury developments being built around them, he says. “The questions come: Why do we conserve when there are golf courses or surfing … in the desert?”

(Burritt, the CVWD representative, notes that the water district “encourages all customers, not just residents, to use water responsibly” and adds that CVWD’s strategic plans project that there should be enough water to serve both the district’s golf courses and its surf pools.)

Locals opposing these projects, meanwhile, argue that developers are grossly underestimating their water use, and various engineering firms and some county officials have in fact offered projections that differ from the developers’ estimates. Opponents are specifically concerned about the effects of spray, evaporation, and other factors, which increase with higher temperatures, bigger waves, and larger pool sizes.

As a rough point of reference, Slater’s 14-acre wave pool in Lemoore, California, can lose up to 250,000 gallons of water per day to evaporation, according to Adam Fincham, the engineer who designed the technology. That’s roughly half an Olympic swimming pool.

More fundamentally, critics take issue with even debating whether surf clubs or golf courses are worse. “We push back against all of it,” says Ambriz, who organized opposition to TBC and argues that neither the pool nor an exclusive new golf course in Thermal benefits the local community. Comparing them, she says, obscures greater priorities, like the water needs of households.