The race to get next-generation solar technology on the market

![]()

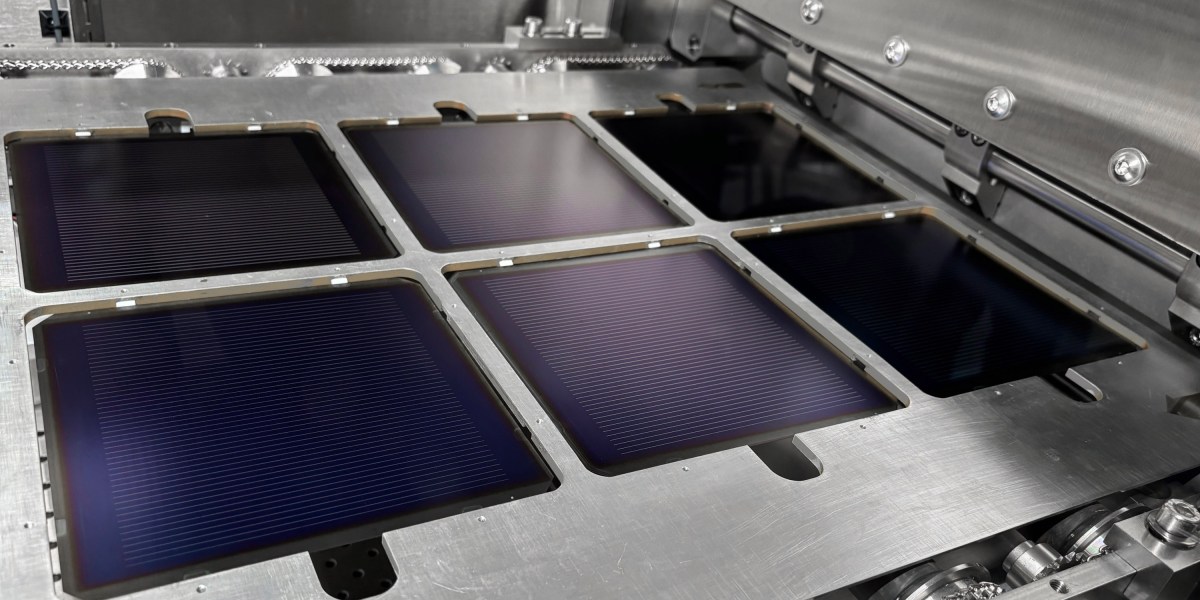

But the industry must ensure that every cell will be that durable; worldwide, companies manufacture hundreds of millions of solar panels every year, each containing dozens of cells. Before they’re used in projects, panels must pass rigorous industry tests, like enduring quick temperature changes, humidity, and hail. Swift, which was founded in 2017, hasn’t started independent tests yet; for now it’s subjecting its cells to some of those conditions in its own lab and has one panel wired up on its roof.

Startups like Swift and Oxford PV—a UK company spun out of a university research lab where some Swift founders once worked—are working alongside the industry’s largest companies to get tandems to market. Oxford PV says it will start shipping perovskite tandem panels to customers later this year. In May, Arizona-based First Solar, the largest solar manufacturer in the US, bought a European perovskite company called Evolar.

In a release on its Evolar acquisition, First Solar CEO Mark Widmar said the company believes “high-efficiency tandem PV modules will define the future.” Just a few days later, Korea-based Hanwha Q Cells, another top manufacturer, said it was investing $100 million to set up a perovskite tandem pilot line. In 2022, Q Cells helped start Pepperoni, a European collaboration to advance tandems.

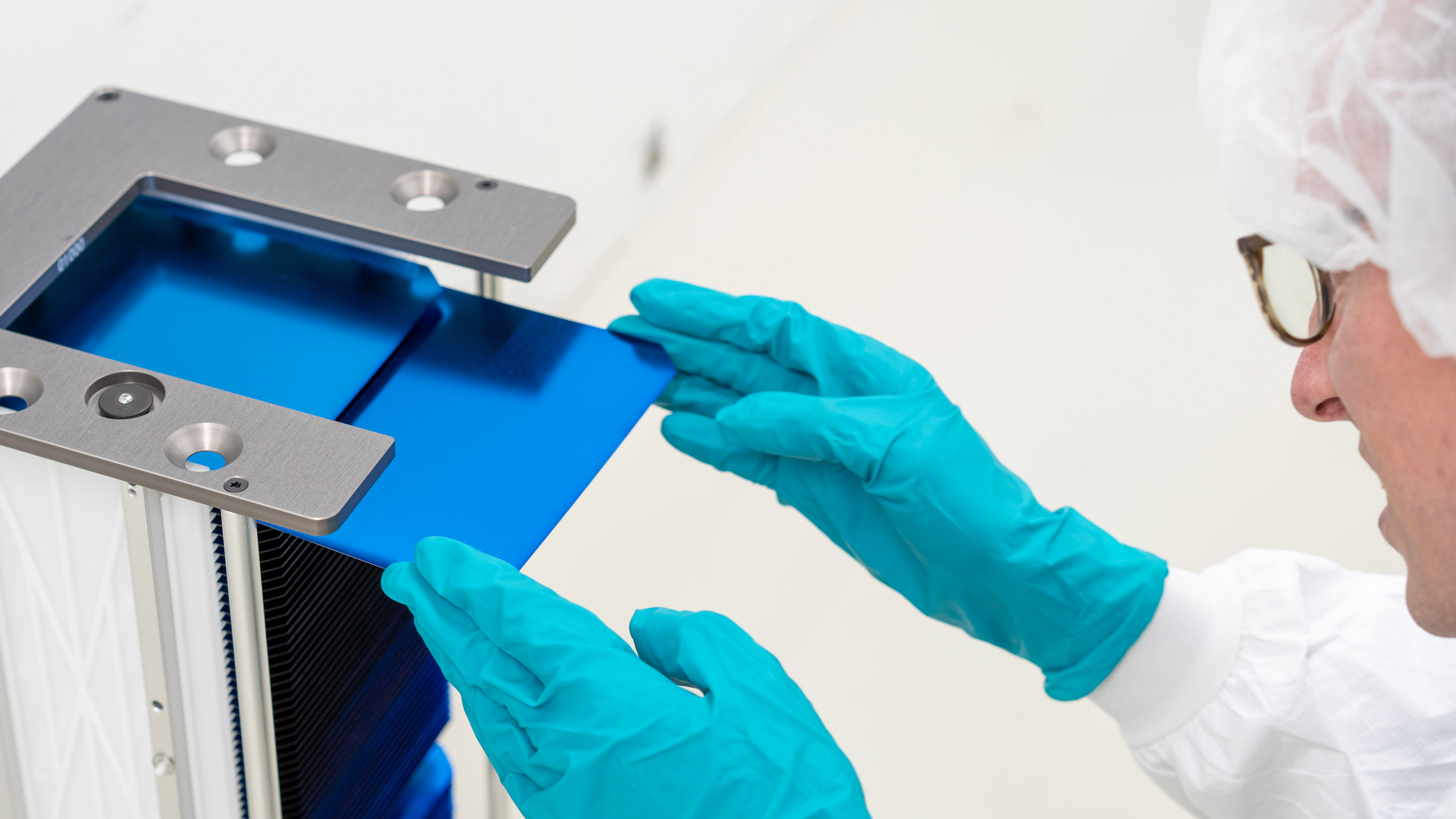

DAVID MALCOM/OXFORD PV

Researchers working on perovskites say commercial tandem cells could be years, not decades, away. Jean says Swift hopes to have a product ready to commercialize within four years. Incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act, which included credits for US-made clean energy products, should help.

But perovskites have skeptics as well as supporters. Chase says today’s silicon panels are already good enough to help the world transition to clean energy and fight climate change. She has long questioned perovskites’ ability to upend the solar industry’s status quo.“You cannot make a semiconductor tech with momentum,” she says. “You need the tech to work.”

Given how much solar energy will be needed to decarbonize the grid, however, perovskite backers say every bit of added efficiency will be important.

“While it’s true that silicon is great, tandems are better,” says Leijtens. “In the fight to tackle climate change, we need to accelerate, not just say, ‘Oh, this is good enough—we’re done.’ Everything can continue to be improved.”