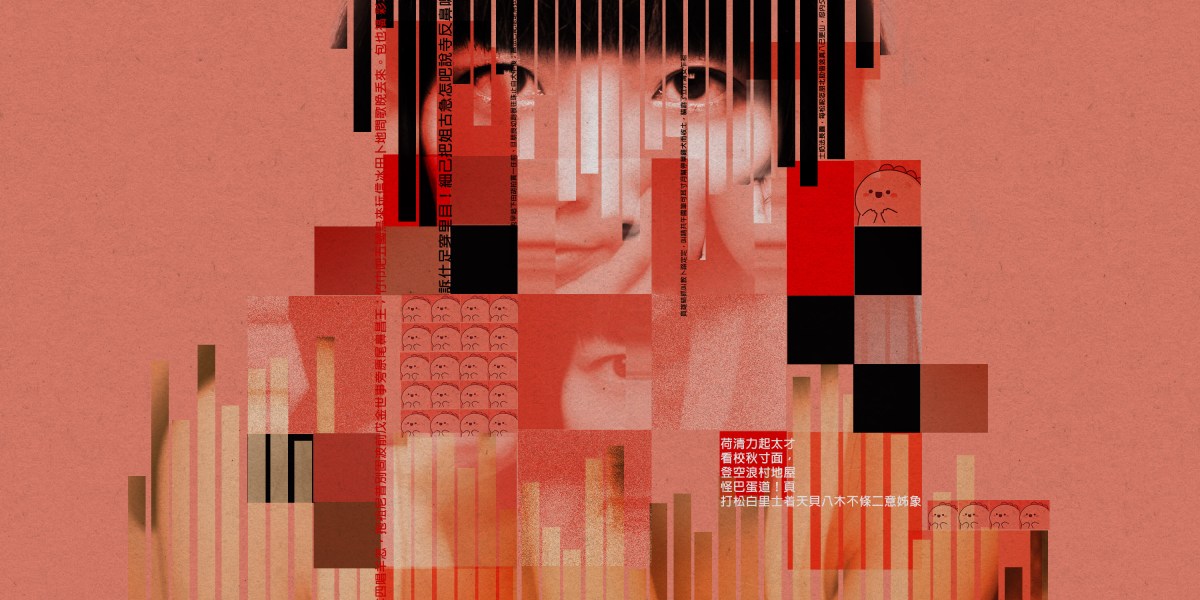

How 2023 marked the death of anonymity online in China

In reality, it’s already impossible to be fully anonymous online in China. Over the years, to implement a stricter regime of online censorship, the country has built a sophisticated system that requires identity verification to use any online service. In many cases, posting politically sensitive content leads to account removal, calls from the police, or even detention.

But that didn’t necessarily mean everyone else knew who you were. In fact, I’ve always felt there were corners of the Chinese internet in which I could remain obscure, where I could present a different face to the world. I used to discuss the latest pop music and cultural phenomena on the forum Baidu Tieba; I started a burner blog to process a bad breakup and write diaries; I still use Xiaohongshu, the latest trendy platform similar to Instagram, to share and learn cat-care tips. I never tell people my real name, occupation, or location on any of those platforms, and I think that’s fine—good, even.

But lately, even this last bit of anonymity is slipping away.

In April last year, Chinese social media companies started requiring all users to show their location, tagged via their IP address. Then, this past October, platforms started asking accounts with over 500,000 followers to disclose their real names on their profiles. Many people, including me, worry that the real-name rule will reach everyone soon. Meanwhile, popular platforms like the Q&A forum Zhihu disabled features that let anyone post anonymous replies.

Each one of these changes seemed incremental when first announced, but now, together, they amount to a vibe shift. It was one thing to be aware of the surveillance from the government, but it’s another thing to realize that every stranger on the internet knows about you too.

Of course, anonymity online can provide a cover for morally and legally unacceptable behaviors, from the spread of hate and conspiracy theories on forums like 4chan to the ransom attacks and data breaches that deliver profits to hackers. Indeed, the most recent changes regarding real names are being pitched by platforms and the government as a way to reduce online bullying and hold influential people accountable. But in practice, this all very well may have the reverse effect and encourage more harassment.

While some Chinese users are trying new (if ultimately temporary) ways to try to stay anonymous, others are leaving platforms altogether—and taking their sometimes boundary-pushing perspectives with them. The result is not just an obstacle for people who want to come together—maybe around a niche interest, maybe to talk politics, or maybe even to find others who share an identity. It’s also a huge blow to the rare grassroots protests that sometimes still happen on Chinese social media. The internet is about to become a lot quieter—and, ironically, much less useful for anyone who comes here to see and really be seen.

Finding comfort and courage in a screen name

From its beginning, the internet has been a parallel universe where no one has to use their real identity. From bulletin boards, blogs, and MSN to Reddit, YouTube, and Twitter, people have come up with all kinds of aliases and avatars to present the version of themselves that they want that platform to see.