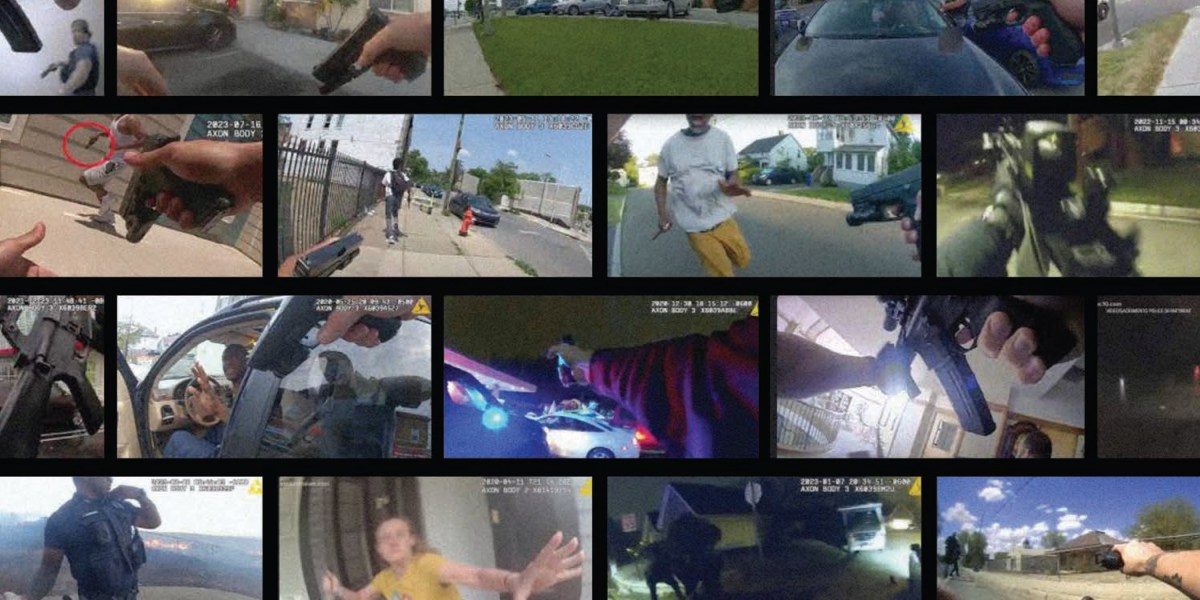

AI was supposed to make police bodycams better. What happened?

Tassone claims that Truleo, which hit the market in 2021, can identify events like an officer frisking someone or reading Miranda rights to a suspect, and calculate a professionalism score. The software doesn’t eliminate human review, he says; it augments it. Police chiefs or supervisors set up lists of keywords or events, get emails and notifications when the system detects these triggers, and then review the footage. Truleo’s tech is installed on department servers, so the data remains sequestered.

In the company’s own studies, Tassone claims, officers monitored by Truleo always score better than the control group; a study of one client, the police department in Alameda, California, found a 36% reduction in uses of force. No third-party analyses of Truleo have yet been completed; researchers at the nonprofit RTI are currently studying its analysis of bodycam footage from Georgia state parole and probation officers, but results aren’t expected anytime soon. Secure Justice, a nonprofit based in Oakland, California, that focuses on police tech and abuses of power, briefly considered pushing a bill to mandate the use of Truleo across the state, but executive director Brian Hofer says the group hadn’t “done sufficient due diligence at this stage to be comfortable making an aggressive move like that” and may revisit the idea in 2025.

“It just opens up law enforcement’s frame of surveillance in a way that we haven’t really previously had to deal with.”

Beryl Lipton, investigative researcher, Electronic Frontier Foundation

Still, Hofer suspects the technology does work. In fact, that very efficacy may be one reason it hasn’t been universally welcomed: drama has erupted within two police departments that used and then dropped Truleo. In Vallejo, California, officers and police union officials objected to the introduction of the technology, with its potential to reveal unsavory behavior, and blamed it for inaccuracies and labor violations. The controversy helped accelerate the departure of the department’s reformist chief, Shawny Williams, last July. In Seattle, where the police department also canceled its contract with Truleo amid union objections, an officer was caught on bodycam footage last fall mocking a woman’s death; Truleo had flagged the incident.

Police officers aren’t the only ones with reasons to question this technology, though. The growing use of bodycam-to-text programs, along with increased use of cameras and drones, further normalizes surveillance by law enforcement, adding more everyday interactions to a searchable, indexable database. Jennifer Lee, former manager of the technology and liberty project at the ACLU of Washington, said in a statement that “the potential to use AI technology for purposes other than accountability raises significant questions that must be addressed.”

“It just opens up law enforcement’s frame of surveillance in a way that we haven’t really previously had to deal with so much but increasingly have to deal with constantly,” says Beryl Lipton, an investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital rights group. The recording, transcription, and cataloguing of what someone says on the street in public during interactions with police raises a red flag, she says. She also points to concerns about bias and inaccuracy in the technology itself that arose when phone calls from prisoners were recorded, analyzed, and later made searchable via AI.

It’s difficult to fully address such concerns because, as with many AI systems, the exact way these bodycam-to-text systems work remains opaque, and it’s all the more so when outsiders can’t know what terms police departments are searching for. Besides, the significance of their findings depends on context, says Rob Voigt, a Northwestern University researcher and linguistics expert, who coauthored a 2017 paper that used bodycam footage to measure racial disparities in police attitudes toward minorities.