The many uses of mini-organs

An ultrasound, for example, might reveal that a fetus’s kidneys are smaller than they should be, but absent a glaring genetic defect, doctors can’t say why they’re small or figure out a fix. But if they can take a small sample of amniotic fluid and grow a kidney organoid, the problem might become evident, and so might a potential solution.

Exciting, right? But organoids can do so much more!

Let’s do a roundup of some of the weird, wild, wonderful, and downright unsettling uses that researchers have come up with for organoids.

Organoids could help speed drug development. By some estimates, 90% of drug candidates fail during human trials. That’s because the preclinical testing happens largely in cells and rodents. Neither is a perfect model. Cells lack complexity. And mice, as we all know, are not humans.

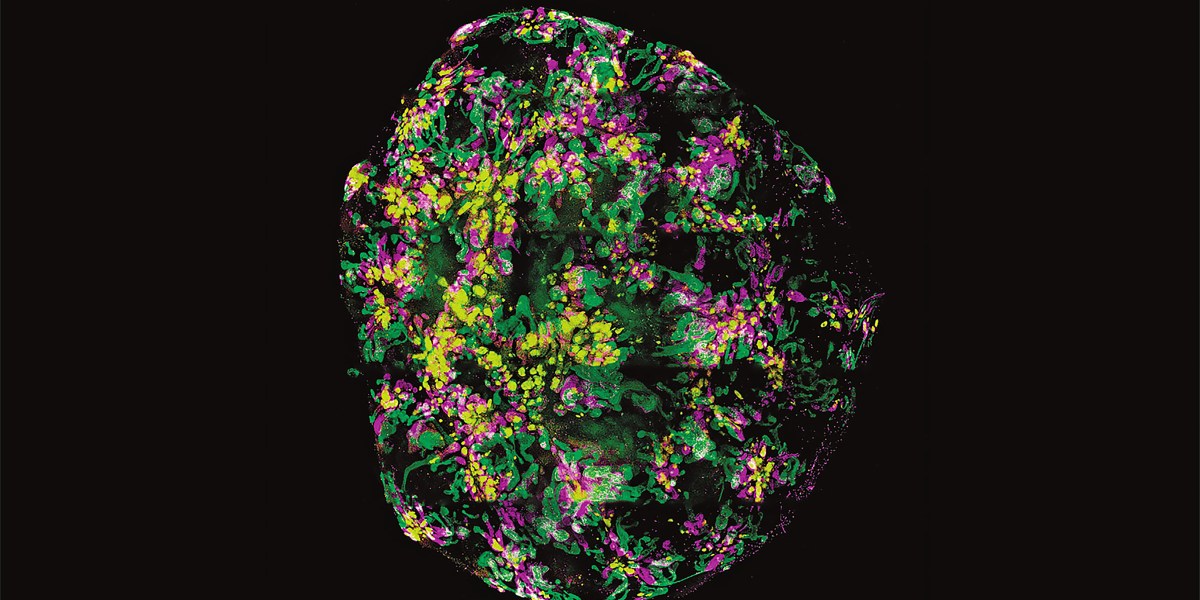

Organoids aren’t humans either, but they come from humans. And they have the advantage of having more complexity than a layer of cells in a dish. That makes them a good model for screening drug candidates. When I wrote about organoids in 2015, one cancer researcher told me that studying cells to understand how an organ functions is like studying a pile of bricks to understand the function of a house. Why not just study the house?

Big Pharma appears to agree. In 2022, Roche hired organoid pioneer Hans Clevers to head its Pharma Research and Early Development division. “My belief is that human organoids will eventually complement everything we are currently doing. I’m convinced, now that I’ve seen how the whole drug development process runs, that one can implement human organoids at every step of the way,” Clevers told Nature.

Organoids are trickier to grow than cell lines, but some companies are working to make the process automated. The Philadelphia-based biotech Vivodyne has developed a robotic system that combines organoids with organ-on-a-chip technology. The system grows 20 kinds of human tissue, each containing 200,000 to 500,000 cells, and then doses them with drugs. These “lab-grown human test subjects” provide “huge amounts of complex human data—larger than you could get from any clinical trial,” said Andrei Georgescu, CEO and cofounder of Vivodyne, in a press release.

According to Viodyne’s website, the proprietary machines can test 10,000 independent human tissues at a time, “yielding vivarium-scale output.” Vivarium-scale output. I had to roll this phrase around my brain quite a few times before I understood what they meant: the robot provides the same amount of data as a building full of lab mice.